Chief Gall, also known as Phizí, was a prominent Lakota Sioux leader in the 19th century. Born in 1840, he played a significant role in the Battle of Little Bighorn and later resisted forced relocation to reservations. Known for his leadership, diplomacy, and advocacy for Native American rights and sovereignty, Chief Gall left a lasting legacy among the Lakota Sioux and in Native American history. This article provides an overview of Chief Gall's life, achievements, and contributions to Native American communities, as well as the historical significance of his legacy.

Early Life and Background of Chief Gall

Birth and Childhood

Chief Gall, also known as Pizi or Gal was born in 1840 in the Dakota Territory. His birthplace is believed to be near the present-day town of McLaughlin, South Dakota. Being born during a time of great change and upheaval for indigenous people, Chief Gall grew up witnessing the effects of colonization on his people.

Family and Tribal Connections

Chief Gall belonged to the Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux tribe, which was one of the largest and most prominent Sioux tribes in the Great Plains region. He was the son of Chief Sitting Bear and a member of the Bad Face band of the Hunkpapa. Chief Gall was closely related to other notable Lakota Sioux leaders, such as Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse.

Education and Cultural Upbringing

As a young boy, Chief Gall was trained in the traditional Lakota way of life, which emphasized hunting, gathering, and warfare. He learned important survival skills, such as horseback riding, hunting, and tracking, which would serve him well in his later years. Chief Gall was also taught the importance of preserving Lakota culture and traditions, which he would become a strong advocate for.

Chief Gall's Role in the Battle of Little Bighorn

Overview of the Battle

The Battle of Little Bighorn, which took place on June 25, 1876, was a significant event in the history of indigenous resistance against colonization. It was fought between a coalition of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors led by Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and other chiefs, and the US Army's 7th Cavalry Regiment led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer.

Leadership and Strategy

Chief Gall played a crucial role in the battle, leading a group of warriors who were able to hold off the initial attack of Custer's troops. It was his strategic decision to lead his men to flank the cavalry, which proved to be a turning point in the battle. Although Chief Gall's forces did not deal the final blow to Custer's troops, his leadership and tactical skills were instrumental in the eventual victory of the indigenous coalition.

Impact of the Battle on Chief Gall's Life

Chief Gall's victory at Little Bighorn made him a national hero among the Lakota. However, the aftermath of the battle was devastating for his people. The US government launched a brutal retaliation against the indigenous coalition, leading to the massacre at Wounded Knee, and Chief Gall was forced to flee to Canada to avoid capture. His life would never be the same again.

Imprisonment and Resistance Against Forced Relocation

Arrest and Imprisonment

In 1881, Chief Gall was arrested by the US government and imprisoned at Fort Pickens in Florida for over a year. He was eventually released, but his freedom was short-lived. The US government had initiated a policy of forced relocation of indigenous peoples to reservations, and Chief Gall was among those who refused to comply.

Resistance Against Relocation and the Ghost Dance Movement

Chief Gall was a vocal opponent of the US government's policies and was involved in the Ghost Dance movement, a religious movement that spread among indigenous peoples in the late 19th century. The movement advocated for the restoration of indigenous land and sovereignty and included a ritual dance believed to bring about the return of the bison and the resurrection of the ancestors. Chief Gall's participation in the movement led to further persecution by the US government.

Effects of Resistance on Native American Policy

Chief Gall's resistance and the larger indigenous resistance movement led to changes in US government policy towards Native Americans. A new policy of assimilation rather than forced relocation was adopted, and the government began to recognize the importance of preserving indigenous culture and autonomy.

Chief Gall's Leadership and Legacy Among the Lakota Sioux

Leadership Style and Principles

Chief Gall was known for his bravery, intelligence, and strategic thinking. He was a respected leader among the Lakota Sioux and was admired for his commitment to preserving Lakota culture and traditions. His leadership style was characterized by his ability to inspire and motivate his people, as well as his strong sense of justice and fairness.

Role in Diplomacy and Negotiations

In his later years, Chief Gall became involved in diplomacy and negotiations with the US government. He sought to protect the rights of his people and ensure that their voices were heard in any negotiations. Although he was not always successful, his efforts helped to lay the groundwork for future generations of indigenous leaders.

Influence on Future Generations

Chief Gall's legacy has continued to inspire generations of Lakota Sioux leaders. He remains a symbol of resistance, bravery, and cultural preservation, and his contributions to indigenous rights have had a lasting impact on Native American policy. His courage and perseverance continue to serve as a reminder of the importance of standing up for what one believes in, no matter the cost.

Notable Achievements and Contributions to Native American History

Advocacy for Native American Rights and Sovereignty

Chief Gall was a leader and advocate for the rights and sovereignty of the Lakota people. He fiercely resisted the forced relocation of his tribe to reservations and led battles against the United States government during the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877. Despite being outnumbered, his strategic military tactics and determination earned him the respect of both his people and adversaries.

Preservation of Lakota Culture and Traditions

Chief Gall was committed to preserving the Lakota culture and traditions. He emphasized the importance of passing down the language and customs of his people to future generations. He also actively participated in ceremonial dances and rituals and encouraged others to do the same.

Collaboration and Alliances with Other Indigenous Leaders

Chief Gall recognized the strength in collaboration and formed alliances with other indigenous leaders. He worked closely with Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and other Lakota chiefs during the Great Sioux War. He also established relationships with Cheyenne and Arapaho leaders and fought alongside them during battles against the United States government.

Personal Life and Family of Chief Gall

Marriage and Family

Chief Gall was married to a woman named Dacotah and had several children. His daughter, Paustine, was known for accompanying him into battle and healing wounded warriors.

Interests and Hobbies

Chief Gall enjoyed hunting and spent much of his spare time honing his skills with a bow and arrow. He was also an expert horseman and took pride in training and caring for his horses.

Relationships with Other Tribal Leaders and Figures

Chief Gall had close relationships with other notable Lakota figures such as Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. He also established friendships with Cheyenne and Arapaho leaders such as Chief Roman Nose.

Historical Significance and Remembering Chief Gall

Legacy Among Native American Communities

Chief Gall continues to be remembered and celebrated among Native American communities. His leadership and bravery in battles against the United States government are seen as symbols of resistance and perseverance against oppression.

Representation in Popular Culture and Media

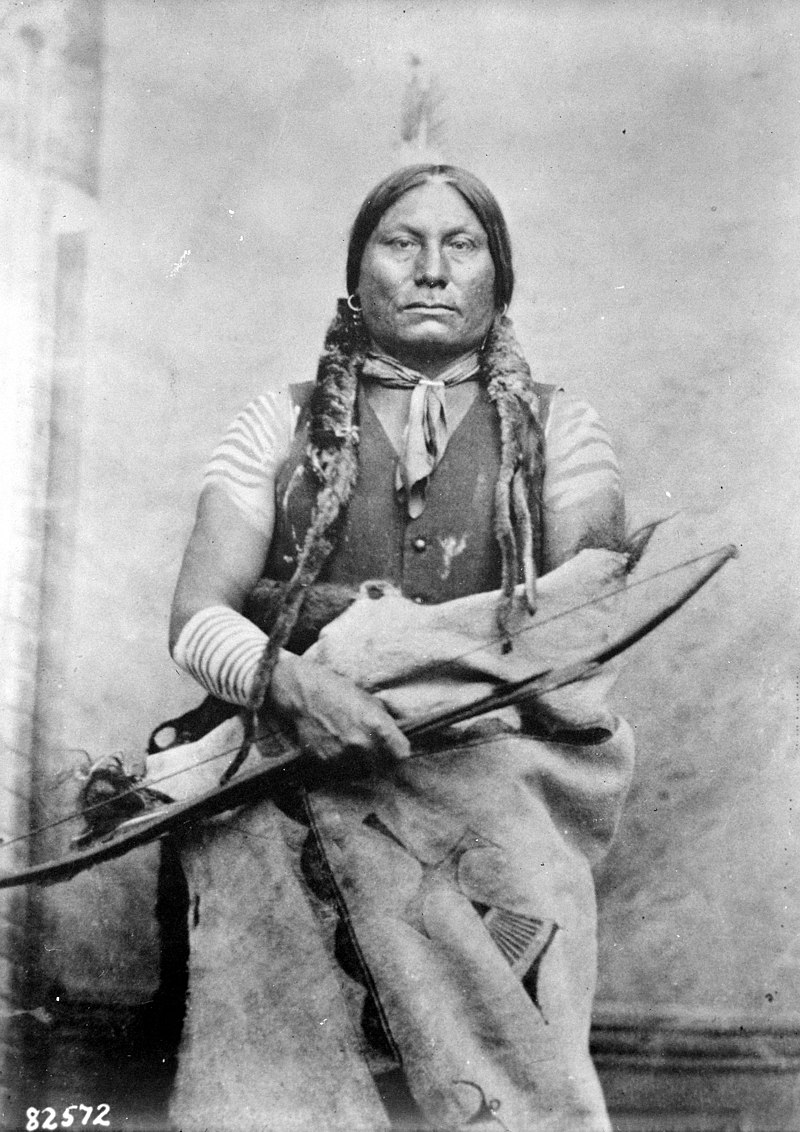

Chief Gall is featured in several historical accounts and textbooks, and his image has been immortalized in artwork and photographs. He has also been portrayed in movies and television shows, including the HBO series "Deadwood."

Memorials and Monuments Honoring Chief Gall

There are several memorials and monuments honoring Chief Gall located throughout the United States. In South Dakota, a monument stands in his honor at the site of the Battle of Little Bighorn.

Impact of Chief Gall's Life and Legacy on Modern Native American Communities

Continued Advocacy for Native American Rights and Sovereignty

Chief Gall's commitment to advocating for the rights and sovereignty of the Lakota people has inspired a new generation of leaders to continue the fight against oppression and injustice.

Preservation and Promotion of Native American Culture and Traditions

Chief Gall's emphasis on preserving the Lakota culture and traditions has been passed down through generations. Today, there are efforts to revitalize the Lakota language and promote traditional practices such as ceremonial dances and rituals.

Remembering Chief Gall as a Symbol of Resistance and Leadership

Chief Gall's life and legacy continue to represent an unwavering spirit of resistance and leadership among Native American communities. He serves as a reminder of the strength and resilience of indigenous people in the face of adversity.Chief Gall's life and legacy continue to inspire and influence modern Native American communities. His leadership, advocacy, and preservation of Lakota culture and traditions have left an enduring impact in Native American history. From his notable achievements to his powerful resistance against forced relocation, Chief Gall's story is a testament to the enduring strength and resilience of Indigenous peoples. We remember Chief Gall as a symbol of resistance, leadership, and a true hero in the struggle for Native American rights and sovereignty.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What was Chief Gall's role in the Battle of Little Bighorn?

Chief Gall was one of the key leaders in the Battle of Little Bighorn, also known as Custer's Last Stand. He played a significant role in the battle strategy and leadership, which ultimately led to the defeat of General Custer and his troops. Chief Gall's military prowess and bravery made him a prominent figure in Native American history.

What was the Ghost Dance Movement?

The Ghost Dance Movement was a religious movement that emerged among Native American communities in the late 19th century. It involved a series of spiritual dances and rituals, with the belief that they would bring about the restoration of the natural world and the return of deceased ancestors. Chief Gall was a significant figure in the movement, and his resistance against forced relocation was partly inspired by the Ghost Dance.

Why is Chief Gall important in Native American history?

Chief Gall is an important figure in Native American history for his leadership, advocacy, and preservation of Lakota culture and traditions. He played a significant role in shaping the history of his people, from the Battle of Little Bighorn to his resistance against forced relocation. Chief Gall's legacy continues to inspire and influence modern Native American communities, serving as a symbol of resistance, leadership, and heroism.

What impact did Chief Gall's resistance have on Native American policy?

Chief Gall's resistance against forced relocation and advocacy for Native American rights and sovereignty had a significant impact on Native American policy. His leadership and activism, along with the efforts of other Indigenous leaders and activists, contributed to changes in government policy towards Native American communities. Today, Chief Gall is remembered as a powerful voice in the struggle for Native American rights and the preservation of Indigenous cultures and traditions.

-------------------------

Chief Gall was one of the most aggressive leaders of the Sioux nation in their last stand for freedom. The westward pressure of civilization during the past three centuries has been tremendous. When our hemisphere was "discovered", it had been inhabited by the natives for untold ages, but it was held undiscovered because the original owners did not chart or advertise it. Yet some of them at least had developed ideals of life which included real liberty and equality to all men, and they did not recognize individual ownership in land or other property beyond actual necessity.

It was a soul development leading to essential manhood. Under this system they brought forth some striking characters. Gall was considered by both Indians and whites to be a most impressive type of physical manhood. From his picture you can judge of this for yourself. Let us follow his trail. He was no tenderfoot. He never asked a soft place for himself. He always played the game according to the rules and to a finish.

To be sure, like every other man, he made some mistakes, but he was an Indian and never acted the coward. The earliest stories told of his life and doings indicate the spirit of the man in that of the boy. When he was only about three years old, the Blackfoot band of Sioux were on their usual roving hunt, following the buffalo while living their natural happy life upon the wonderful wide prairies of the Dakotas. It was the way of every Sioux mother to adjust her household effects on such dogs and pack ponies as she could muster from day to day, often lending one or two to accommodate some other woman whose horse or dog had died, or perhaps had been among those stampeded and carried away by a raiding band of Crow warriors.

On this particular occasion, the mother of our young Sioux brave, Matohinshda, or Bear-Shedding-His-Hair (Gall's childhood name), intrusted her boy to an old Eskimo pack dog, experienced and reliable, except perhaps when unduly excited or very thirsty. On the day of removing camp the caravan made its morning march up the Powder River. Upon the wide table-land the women were busily digging teepsinna (an edible sweetish root, much used by them) as the moving village slowly progressed. As usual at such times, the trail was wide. An old jack rabbit had waited too long in hiding.

Now, finding himself almost surrounded by the mighty plains people, he sprang up suddenly, his feathery ears conspicuously erect, a dangerous challenge to the dogs and the people. A whoop went up. Every dog accepted the challenge.

Forgotten were the bundles, the kits, even the babies they were drawing or carrying. The chase was on, and the screams of the women reechoed from the opposite cliffs of the Powder, mingled with the yelps of dogs and the neighing of horses. The hand of every man was against the daring warrior, the lone Jack, and the confusion was great.

When the fleeing one cleared the mass of his enemies, he emerged with a swiftness that commanded respect and gave promise of a determined chase. Behind him, his pursuers stretched out in a thin line, first the speedy, unburdened dogs and then the travois dogs headed by the old Eskimo with his precious freight. The youthful Gall was in a travois, a basket mounted on trailing poles and harnessed to the sides of the animal.

"Hey! hey! they are gaining on him!" a warrior shouted. At this juncture two of the canines had almost nabbed their furry prey by the back. But he was too cunning for them. He dropped instantly and sent both dogs over his head, rolling and spinning, then made another flight at right angles to the first. This gave the Eskimo a chance to cut the triangle.

He gained fifty yards, but being heavily handicapped, two unladen dogs passed him. The same trick was repeated by the Jack, and this time he saved himself from instant death by a double loop and was now running directly toward the crowd, followed by a dozen or more dogs. He was losing speed, but likewise his pursuers were dropping off steadily. Only the sturdy Eskimo dog held to his even gait, and behind him in the frail travois leaned forward the little Matohinshda, nude save a breech clout, his left hand holding fast the convenient tail of his dog, the right grasping firmly one of the poles of the travois.

His black eyes were bulging almost out of their sockets; his long hair flowed out behind like a stream of dark water. The Jack now ran directly toward the howling spectators, but his marvelous speed and alertness were on the wane; while on the other hand his foremost pursuer, who had taken part in hundreds of similar events, had every confidence in his own endurance.

Each leap brought him nearer, fiercer and more determined. The last effort of the Jack was to lose himself in the crowd, like a fish in muddy water; but the big dog made the one needed leap with unerring aim and his teeth flashed as he caught the rabbit in viselike jaws and held him limp in air, a victor! The people rushed up to him as he laid the victim down, and foremost among them was the frantic mother of Matohinshda, or Gall. "Michinkshe! michinkshe!" (My son! my son!) she screamed as she drew near. The boy seemed to be none the worse for his experience. "Mother!" he cried, "my dog is brave: he got the rabbit!"

She snatched him off the travois, but he struggled out of her arms to look upon his dog lovingly and admiringly. Old men and boys crowded about the hero of the day, the dog, and the thoughtful grandmother of Matohinshda unharnessed him and poured some water from a parfleche water bag into a basin. "Here, my grandson, give your friend something to drink." "How, hechetu," pronounced an old warrior no longer in active service. "This may be only an accident, an ordinary affair; but such things sometimes indicate a career. The boy has had a wonderful ride. I prophesy that he will one day hold the attention of all the people with his doings."

This is the first remembered story of the famous chief, but other boyish exploits foretold the man he was destined to be. He fought many sham battles, some successful and others not; but he was always a fierce fighter and a good loser.

Once he was engaged in a battle with snowballs. There were probably nearly a hundred boys on each side, and the rule was that every fair hit made the receiver officially dead. He must not participate further, but must remain just where he was struck. Gall's side was fast losing, and the battle was growing hotter every minute when the youthful warrior worked toward an old water hole and took up his position there.

His side was soon annihilated and there were eleven men left to fight him. He was pressed close in the wash-out, and as he dodged under cover before a volley of snowballs, there suddenly emerged in his stead a huge gray wolf. His opponents fled in every direction in superstitious terror, for they thought he had been transformed into the animal. To their astonishment he came out on the farther side and ran to the line of safety, a winner! It happened that the wolf's den had been partly covered with snow so that no one had noticed it until the yells of the boys aroused the inmate, and he beat a hasty retreat. The boys always looked upon this incident as an omen.

Gall had an amiable disposition but was quick to resent insult or injustice. This sometimes involved him in difficulties, but he seldom fought without good cause and was popular with his associates. One of his characteristics was his ability to organize, and this was a large factor in his leadership when he became a man.

He was tried in many ways, and never was known to hesitate when it was a question of physical courage and endurance.

He entered the public service early in life, but not until he had proved himself competent and passed all tests. When a mere boy, he was once scouting for game in midwinter, far from camp, and was overtaken by a three days' blizzard.

He was forced to abandon his horse and lie under the snow for that length of time. He afterward said he was not particularly hungry; it was thirst and stiffness from which he suffered most.

One reason the Indian so loved his horse or dog was that at such times the animal would stay by him like a brother. On this occasion Gall's pony was not more than a stone's throw away when the storm subsided and the sun shone.

There was a herd of buffalo in plain sight, and the young hunter was not long in procuring a meal. This chief's contemporaries still recall his wrestling match with the equally powerful Cheyenne boy, Roman Nose, who afterward became a chief well known to American history.

It was a custom of the northwestern Indians, when two friendly tribes camped together, to establish the physical and athletic supremacy of the youth of the respective camps. The "Che-hoo-hoo" is a wrestling game in which there may be any number on a side, but the numbers are equal.

All the boys of each camp are called together by a leader chosen for the purpose and draw themselves up in line of battle; then each at a given signal attacks his opponent. In this memorable contest, Matohinshda, or Gall, was placed opposite.

written by Charles Eastmen, 1913