Title: Geronimo: The Life and Legacy of an Apache Warrior

Introduction:

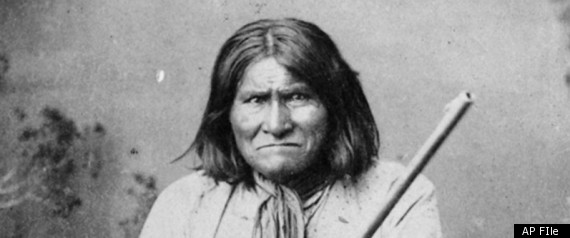

Geronimo, born Goyahkla in 1829, was a prominent leader and medicine man from the Bedonkohe band of the Apache tribe. He fought against the encroachment of Mexican and American settlers on his people's traditional lands in the American Southwest, becoming a symbol of resistance for the Apache and a legendary figure in the annals of American history. Geronimo's life was marked by conflict, tragedy, and an unwavering determination to protect his people's way of life.

Chapter 1: Early Life and the Bedonkohe Apache

Geronimo was born in No-Doyohn Canon, Arizona, in 1829, to a family of Bedonkohe Apache, one of the many bands that formed the larger Chiricahua Apache tribe. The chapter provides an overview of the Bedonkohe's traditional lifestyle, their nomadic existence, and their reliance on hunting, gathering, and raiding for sustenance.

Chapter 2: Tragedy and Revenge

In 1858, a turning point in Geronimo's life occurred when his wife, children, and mother were murdered by Mexican soldiers in a surprise attack. Devastated by the loss, Geronimo embarked on a path of vengeance and war, dedicating himself to fighting against the Mexican and American forces that threatened his people's existence.

Chapter 3: The Rise of a Warrior

As Geronimo rose through the ranks of the Apache tribe, he became known for his bravery, tactical acumen, and uncanny ability to avoid capture. This chapter details Geronimo's campaigns against the Mexican and American armies, as well as the various skirmishes he fought alongside other famous Apache leaders like Cochise and Mangas Coloradas.

Chapter 4: The Final Campaigns

Between 1876 and 1886, Geronimo and his band of followers continued to resist American and Mexican forces. This chapter discusses the final years of Geronimo's resistance, including the signing of the 1886 peace treaty, his subsequent capture, and his ultimate surrender to General Nelson A. Miles.

Chapter 5: Life as a Prisoner of War

Following his surrender, Geronimo was labeled a prisoner of war and was moved to various locations, including Florida, Alabama, and eventually Oklahoma. The chapter discusses the harsh conditions the Apache prisoners faced, the struggle to maintain their cultural identity, and the slow disintegration of the Apache community.

Chapter 6: Geronimo's Twilight Years

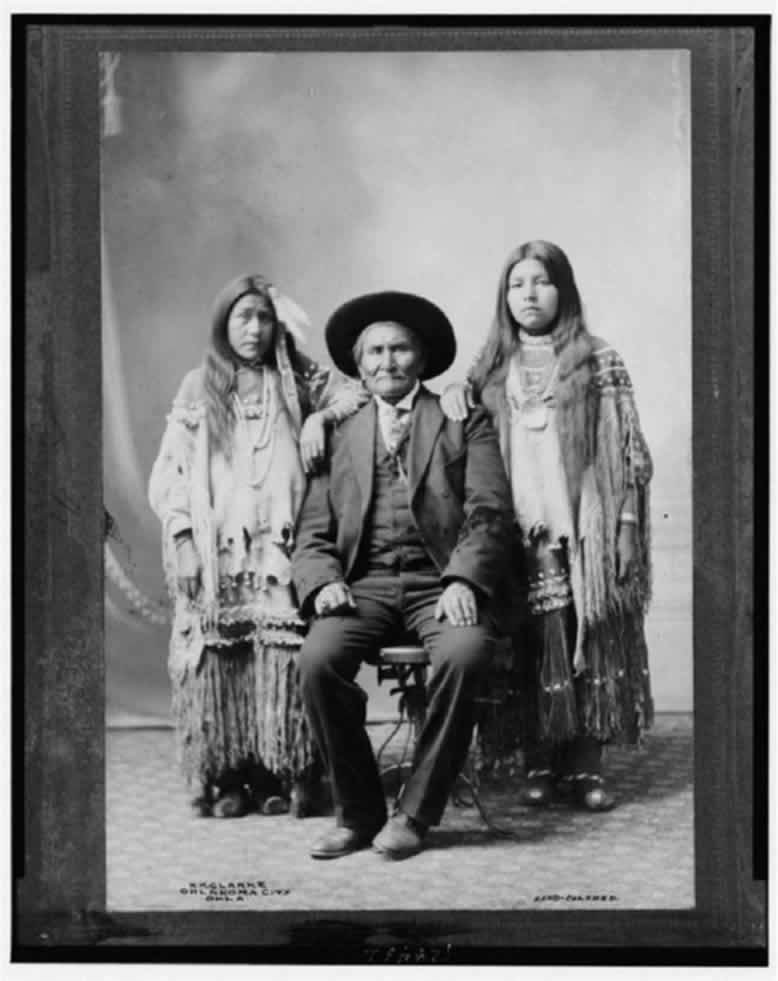

In his final years, Geronimo became a public figure, attending events like the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904 and President Theodore Roosevelt's inauguration in 1905. This chapter explores Geronimo's life as a celebrity, his final years in captivity, and the challenges he faced in coming to terms with the transformation of his people's way of life.

Conclusion: Geronimo's Legacy

Geronimo passed away on February 17, 1909, at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Despite his status as a prisoner of war, he remained a symbol of resistance for the Apache people and an inspiration for future generations. The conclusion reflects on Geronimo's enduring legacy, the historical significance of his life, and the ongoing struggle for Native American rights and recognition.

_______________________________

Native name Goyaałé, "one who yawns"; often spelled Goyathlay or Goyahkla

June 16, 1829

Tribe Bedonkohe Apache

February 17, 1909

Gila River, Bedonkoheland under Mexican occupation

![]()

Geronimo (Mescalero-Chiricahua: Goyaałé [kòjàːɬɛ́] "one who yawns";aged 79)) was a prominent leader of the Bedonkohe Apache who fought against Mexico and the United States for their expansion into Apache tribal lands for several decades during the Apache Wars. "Geronimo" was the name given to him during a battle with Mexican soldiers. His Chiricahua name is often rendered as Goyathlay or Goyahkla in English.

)http://www.biography.com/people/geronimo-9309607/videos/geronimo-full-episode-2073241850

After an attack by a company of Mexican soldiers killed his mother, wife and three children in 1858, Geronimo joined revenge attacks on the Mexicans. During his career as a war chief, he was notorious for consistently urging raids upon Mexican Provinces and their towns, and later against American locations across Arizona, New Mexico and western Texas.

In 1886 Geronimo surrendered to U.S. authorities after a lengthy pursuit. As a prisoner of war in old age he became a celebrity and appeared in fairs but was never allowed to return to the land of his birth. He later regretted his surrender and claimed the conditions he made had been ignored. Geronimo died in 1909 from complications of pneumonia at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geronimo

Born in June 1829, in No-Doyohn Canyon, Mexico, Geronimo continued the tradition of the Apaches resisting white colonization of their homeland in the Southwest, participating in raids into Sonora and Chihuahua in Mexico. After years of war Geronimo finally surrendered to U.S. troops in 1886. While he became a celebrity, he spent the last two decades of his life as a prisoner of war.

Early Years

A legend of the untamed American frontier, the Apache leader Geronimo was born in June 1829 in No-Doyohn Canyon, Mexico. He was a naturally gifted hunter, who, the story goes, as a boy swallowed the heart of his first kill in order to ensure a life of success on the chase.

Being on the run certainly defined Geronimo's way of life. He belonged to the smallest band within the Chiricahua tribe, the Bedonkohe. Numbering a little more than 8,000, the Apaches were surrounded by enemies—not just Mexicans, but also other tribes, including the Navajo and Comanches.

Raiding their neighbors was also a part of the Apache life. In response the Mexican government put a bounty on Apache scalps, offering as much as $25 for a child's scalp. But this did little to deter Geronimo and his people. At the age of 17 Geronimo had already led four successful raiding operations.

Around this same time Geronimo fell in love with a woman named Alope. The two married and had three children together.

Then tragedy struck. While out on a trading trip, Mexican soldiers attacked his camp. Word of the ransacking soon reached the Apache men. Quietly that night, Geronimo returned home, where he found his mother, wife and three children all dead.

Warrior Leader

The murders devastated Geronimo. In the tradition of the Apache, he set fire to his family's belongings and then, in a show of grief, headed into the wilderness to bereave the deaths. There, it's said, alone and crying, a voice came to Geronimo that promised him: "No gun will ever kill you. I will take the bullets from the guns of the Mexicans … and I will guide your arrows."

Backed by this sudden knowledge of power, Geronimo rounded up a force of 200 men and hunted down the Mexican soldiers who killed his family. On it went like this for 10 years, as Geronimo exacted revenge against the Mexican government.

Beginning in the 1850s, the face of his enemy changed. Following the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848, the U.S. took over large tracts of territory from Mexico, including areas belonging to the Apache. Spurred by the discovery of gold in the Southwest, settlers and miners streamed into their lands. Naturally, tensions mounted. The Apaches stepped up their attacks, which included brutal ambushes on stagecoaches and wagon trains.

But the Chiricahua leader, Geronimo's father-in-law, Cochise, could see where the future was headed. In an act that greatly disappointed his son-in-law, the revered chief called a halt to his decade-long war with the Americans and agreed to the establishment of a reservation for his people on a prized piece of Apache property.

But within just a few years, Cochise died, and the federal government reneged on its agreement, moving the Chiricahua north so that settlers could move into their former lands. This act only further incensed Geronimo, setting off a new round of fighting.

Geronimo proved to be as elusive as he was aggressive. However, authorities finally caught up with him in 1877 and sent him to the San Carlos Apache reservation. For four long years he struggled with his new reservation life, finally escaping in September 1881.

Out on his own again, Geronimo and a small band of Chiricahua followers eluded American troops. Over the next five years they engaged in what proved to be the last of the Indian wars against the U.S.

Perceptions of Geronimo were nearly as complex as the man himself. His followers viewed him as the last great defender of the Native American way of life. But others, including fellow Apaches, saw him as a stubborn holdout, violently driven by revenge and foolishly putting the lives of people in danger.

With his followers in tow, Geronimo shot across the Southwest. As he did, the seemingly mystical leader was transformed into a legend as newspapers closely followed the Army's pursuit of him. At one point nearly a quarter of the Army's forces—5,000 troops—were trying to hunt him down.

Finally, in the summer of 1886, he surrendered, the last Chiricahua to do so. Over the next several years Geronimo and his people were bounced around, first to a prison in Florida, then a prison camp in Alabama, and then Fort Sill in Oklahoma. In total, the group spent 27 years as prisoners of war.

Final Years

While he and the rest of the Chiricahua remained under guard, Geronimo experienced a bit of celebrity from his white former enemies. Less than a decade after he'd surrendered, crowds longed to catch a glimpse of the famous Indian warrior. In 1905 he published his autobiography, and that same year he received a private audience with President Theodore Roosevelt, unsuccessfully pressing the American leader to let his people return to Arizona.

His death came four years later. While riding home in February 1909, he was thrown from his horse. He survived a night out in the cold, but when a friend found him the next day, Geronimo's health was rapidly deteriorating. He passed away six days later, with his nephew at his side.

"I should never have surrendered," Geronimo, still a prisoner of war, said on his deathbed. "I should have fought until I was the last man alive."

The audio recording of the autobiography by Geronimo

Geronimo

Goyathlay ("one who yawns")

Quotes from Geronimo

"I was warmed by the sun, rocked by the winds and sheltered by the trees as other Indian babes. I was living peaceably when people began to speak bad of me. Now I can eat well, sleep well and be glad. I can go everywhere with a good feeling.

The soldiers never explained to the government when an Indian was wronged, but reported the misdeeds of the Indians. We took an oath not to do any wrong to each other or to scheme against each other.

I cannot think that we are useless or God would not have created us. There is one God looking down on us all. We are all the children of one God. The sun, the darkness, the winds are all listening to what we have to say.

When a child, my mother taught me to kneel and pray to Usen for strength, health, wisdom and protection. Sometimes we prayed in silence, sometimes each one prayed aloud; sometimes an aged person prayed for all of us... and to Usen.

I was born on the prairies where the wind blew free and there was nothing to break the light of the sun. I was born where there were no enclosures."

Geronimo {jur-ahn'-i-moh}, or Goyathlay ("one who yawns"), was born in 1829 in what is today western New Mexico, but was then still Mexican territory. He was a Bedonkohe Apache (grandson of Mahko) by birth and a Net'na during his youth and early manhood. His wife, Juh, Geronimo's cousin Ishton, and Asa Daklugie were members of the Nednhi band of the Chiricahua Apache.

He was reportedly given the name Geronimo by Mexican soldiers, although few agree as to why. As leader of the Apaches at Arispe in Sonora, he performed such daring feats that the Mexicans singled him out with the sobriquet Geronimo (Spanish for "Jerome"). Some attributed his numerous raiding successes to powers conferred by supernatural beings, including a reputed invulnerability to bullets.

Geronimo's war career was linked with that of his brother-in-law, Juh, a Chiricahua chief. Although he was not a hereditary leader, Geronimo appeared so to outsiders because he often acted as spokesman for Juh, who had a speech impediment.

Geronimo was the leader of the last American Indian fighting force formally to capitulate to the United States. Because he fought against such daunting odds and held out the longest, he became the most famous Apache of all. To the pioneers and settlers of Arizona and New Mexico, he was a bloody-handed murderer and this image endured until the second half of this century.

To the Apaches, Geronimo embodied the very essence of the Apache values, agressiveness, courage in the face of difficulty. These qualities inspired fear in the settlers of Arizona and New Mexico. The Chiricahuas were mostly migratory following the seasons, hunting and farming. When food was scarce, it was the custom to raid neighboring tribes. Raids and vengeance were an honorable way of life among the tribes of this region.

By the time American settlers began arriving in the area, the Spanish had become entrenched in the area. They were always looking for Indian slaves and Christian converts. One of the most pivotal moments in Geronimo's life was in 1858 when he returned home from a trading excursion into Mexico. He found his wife, his mother and his three young children murdered by Spanish troops from Mexico. This reportedly caused him to have such a hatred of the whites that he vowed to kill as many as he could. From that day on he took every opportunity he could to terrorize Mexican settlements and soon after this incident he received his power, which came to him in visions. Geronimo was never a chief, but a medicine man, a seer and a spiritual and intellectual leader both in and out of battle. The Apache chiefs depended on his wisdom.

When the Chiricahua were forcibly removed (1876) to arid land at San Carlos, in eastern Arizona, Geronimo fled with a band of followers into Mexico. He was soon arrested and returned to the new reservation. For the remainder of the 1870s, he and Juh led a quiet life on the reservation, but with the slaying of an Apache prophet in 1881, they returned to full-time activities from a secret camp in the Sierra Madre Mountains.

In 1875 all Apaches west of the Rio Grande were ordered to the San Carlos Reservation. Geronimo escaped from the reservation three times and although he surrendered, he always managed to avoid capture. In 1876, the U.S. Army tried to move the Chiricahuas onto a reservation, but Geronimo fled to Mexico eluding the troops for over a decade. Sensationalized press reports exaggerated Geronimo's activities, making him the most feared and infamous Apache. The last few months of the campaign required over 5,000 soldiers, one-quarter of the entire Army, and 500 scouts, and perhaps up to 3,000 Mexican soldiers to track down Geronimo and his band.

In May 1882, Apache scouts working for the U.S. army surprised Geronimo in his mountain sanctuary, and he agreed to return with his people to the reservation. After a year of farming, the sudden arrest and imprisonment of the Apache warrior Ka-ya-ten-nae, together with rumors of impending trials and hangings, prompted Geronimo to flee on May 17, 1885, with 35 warriors and 109 women, children and youths. In January 1886, Apache scouts penetrated Juh's seemingly impregnable hideout. This action induced Geronimo to surrender (Mar. 25, 1886) to Gen. George CROOK. Geronimo later fled but finally surrendered to Gen. Nelson MILES on Sept. 4, 1886. The government breached its agreement and transported Geronimo and nearly 450 Apache men, women, and children to Florida for confinement in Forts Marion and Pickens. In 1894 they were removed to Fort Sill in Oklahoma. Geronimo became a rancher, appeared (1904) at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, sold Geronimo souvenirs, and rode in President Theodore Roosevelt's 1905 inaugural parade.

Geronimo's final surrender in 1886 was the last significant Indian guerrilla action in the United States. At the end, his group consisted of only 16 warriors, 12 women, and 6 children. Upon their surrender, Geronimo and over 300 of his fellow Chiricahuas were shipped to Fort Marion, Florida. One year later many of them were relocated to the Mt. Vernon barracks in Alabama, where about one quarter died from tuberculosis and other diseases. Geronimo died on Feb. 17, 1909, a prisoner of war, unable to return to his homeland. He was buried in the Apache cemetery at:

Fort Sill, Oklahoma

437 Quanah Road

Fort Sill, OK (73503-5000)